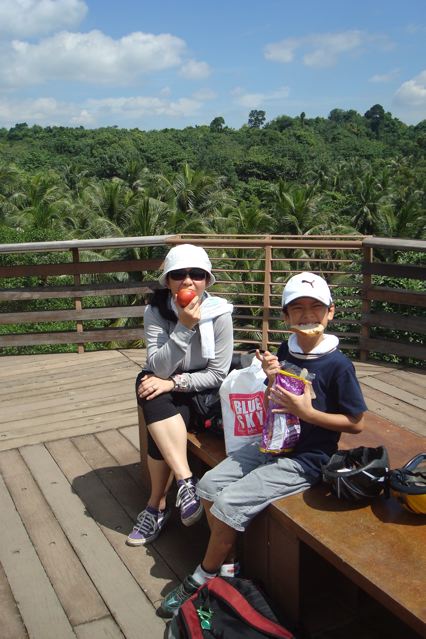

Got groovy goodies in the mail today from Amazon: Leonard Cohen “Live in London” DVD, Chris Bell’s “I Am The Cosmos” CD, Cathedral’s “Garden of Equilibrium/Soul Sacrifice” CD/DVD set, and the 33 1/3 book on Nick Drake’s “Pink Moon.” I’m already watching the Leonard Cohen DVD, and I notice that it’s regionless – awesome! Get rid of that region nonsense. Shirts and pants don’t disallow you from wearing them if you’ve bought them in other countries, why should DVDs lock up if you bought them elsewhere?

Saw a dude wearing an AC/DC t-shirt (“Highway to Hell” cover) at Clementi MRT station pushing a baby stroller with no baby in it – mysterious.

Took Naoko’s CD player to the repair uncle today, got it fixed, but by the time I got it back home it wouldn’t play again. What’s going on? I have to take it again tomorrow morning. It’s no fun getting into a crowded train with a bunch of stuff to carry, but what choice do I have?

CD reviews

CB IATC

Chris Bell, “I am the Cosmos” – Chris Bell was, along with Alex Chilton, one of singer/songwriter/guitarists of the seminal cult band Big Star. He left after the band’s first album, the audaciously-named “#1 Record”, flopped. In the six years he had left to live, he released one single, “I Am The Cosmos” with the “You And Your Sister” B-side, but continued recording. He died in a motorcycle crash in 1978. Over the next 14 years, his stray recordings were gathered and put out on this 1992 release. There are 12 original songs on the release, with the addition of a slow version of “I Am The Cosmos”, and country and acoustic versions of “You And Your Sister.” All of them are good. The two songs from the single also appear on the “Keep An Eye On The Sky” Big Star box set; that set also includes a live and a demo version of “There Was A Light” from 1973, Chris Bell’s version of which appears on this release.

The songs are mostly good, and sound very Paul McCartney-esque (Chris apparently once met Sir Paul in France, a truly big star, after Bell’s Big Star days were done). The CD opens with its powerful, hoary, spooky title track, then gets into the gloomy, sludgy “Better Save Yourself.” “Speed of Sound” is an acoustic, drumless strummer that sounds like it was lifted right off a Big Star album. Later on there’s some light percussion and a really weird keyboard sound. “Get Away” is a jaunty rocker with some truly bizarre drumming. “You And Your Sister” is a beautiful song, although maybe a bit overproduced with bleating “woah woah”, and a grinding cello. Happily, the country and acoustic versions delete these, the arrangements getting sparer and sparer as they go along – the acoustic version is the best. “Make a Scene” is a groovy, catchy pop-rocker, but a little dull. “Look Up” is another cosmic song, full of sweet melodies and light acoustic guitar. “I Got Kinda Lost” is a sweet rocker with a good pace and simple lyrics. “Fight at the Table” is a groovy rocker with a cool bass sound, juke joint piano, and scorching vocals that roar like Paul McCartney’s on “Oh! Darling.” Ditto for “I Don’t Know”, which sounds like it would have been at home on either of the first two Big Star albums. Closing song “Though I Know She Lies” is a sappy tune that, unfortunately, sounds more like the mellowest of Chris DeBurgh ballads (ewwww…). Nice solo, at least, and later in the song Bell wrings some powerful emotion out of his sad lyrics. But having this song at the end of the list doesn’t sour the album, since tacked onto the end are still the alternate versions of “I Am The Cosmos” (which comes in a “slow” version – as if it could be any slower than the original) and “You And Your Sister,” still the real winners of the release.

Other bands have recorded Chris Bell songs, in particular the two from his single; This Mortal Coil recorded both of them, and Pete Yorn and Scarlett Johansson did “I Am The Cosmos”, but of course none of them sound very good at all, a testament to the strength of the original.

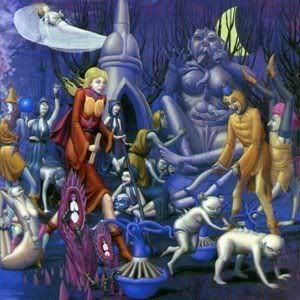

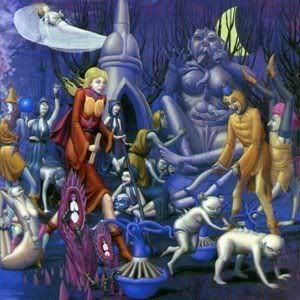

Cathedral Forest of Equilibrium

Cathedral, “Forest of Equilibrium” – I’ve been listening to this release, Cathedral’s first, online for quite some time, but there’s nothing like owning it, especially this gorgeous deluxe re-release that comes with the full remastered first release, the “Soul Sacrifice” EP that followed it, a DVD documentary about the group’s early days, and a poster of the full album art. Gorgeous and grotesque.

The album opens up with the pleasing sounds of a flute, with some medieval-sounding guitar plonkings, very similar to the song “Solitude” on Black Sabbath’s third album “Master of Reality”, which seems to be a favourite of the Cathedral guys – they covered it on the “Nativity in Black” tribute album.

All of the songs plod along at an amazingly slow pace, with the exception perhaps of “Soul Sacrifice”, at a brutally short 2:55 (which, as the rockingest song on the set, is updated and upgraded on the “Soul Sacrifice” EP where it gets a new intro and is lengthened to 4:34 – and even then it would be much shorter than any song on “Garden of Equilibrium”). An odd man out on the album, the song was a forerunner of the faster, rougher stoner sound that the band would later adopt.

“Ebony Tears” has spooky keyboards and bass, then bursts into groans and riffs. That’s the highlight of the song, which drags itself along like a zombie on its last leg. “Serpent Eve” is even sludgier, moving about half as fast. The song ends with what sounds like Mongolian throat singing. Who knew? “A Funeral Request” is a very simple song with nothing special to it. “Equilibrium” is as plodding as the rest of them, but it has a simple, soulful solo that really stands out so powerfully. It also provides the fade-out for the track. More gorgeous than grotesque – superb, really.

The flute of opening track “Pictures of Beauty and Innocence” returns in the final track, “Reaching Happiness, Touching Pain”, and it stays throughout. The song has a very gothic feel to it, sort of like Dead Can Dance, or Xymox.

The “Soul Sacrifice” EP rocks, starting with the title track, which lengthens and livelies up the song from the band’s first release (the new intro is a thread from inside the track). And even in the dredges of “Frozen Rapture,” the drummer manages to break out the cowbell during one more uptempo part – hey, is this Cathedral or is this Foghat.

The DVD is mainly the four members of Cathedral talking about their career, starting with Lee Dorian talking about his roots and how he got into Napalm Death for half of the “Scum” album, before building this new band – which was practically the antithesis of Napalm Death – as a tribute to bands he and his companions adored, bands like The Obsessed, Saint Vitus, Trouble, Candlemass, Witchmaster General, and of course… Black Sabbath. The footage of the lads having a conversation in the pub over beers is interspersed with soundless footage and pictures of those early days, and some live video snippets, to keep it “interesting.” The band talks about the confusion of finding people who wanted to produce a band with the doom sound (deeper, heavier and slower than Black Sabbath, Trouble or Witchfinder General), going through band members (including the drummer of Sacrilege, a favourite band of the guys), and in finding that sound. They considered names like Father, Tower of Silence, Trinity. They walked past a ruined cathedral, and wanted the band to sound like the cathedral looked, and they considered Cathedral of Doom, until they finally realised that just Cathedral was enough. In conversation, the band references Michel Gira of the Swans, Diamanda Galas, Charles Baudelaire, HP Lovecraft (of course). Lee notes that his favourite song from the album was “Equilibrium”, where the lyrics summed up his point of view.

We were going for something that was really quite nihilistic, but in a positive and cleansing way, in the fact that it was so nihilistic that it was almost sarcastic; and then through that, it was quite humorous in some respects, but I don’t think people really saw the humorous side of it.

The band played their first gig in a village in England with SxOxBx from Japan – how did SxOxBx get out there in those early days? Their early gigs were with Agnostic Front and Saint Vitus (!!!!), then they toured outside of England with Paradise Lost. Video of them playing “Soul Sacrifice.” Good vibes – “where is my sleeping bag!” Drinking a lot, smoking lots of pot, getting pretty caned, the other bands on the Gods of Grind tour. “After ten days of free beer you start to lose your mind, really.” At the beginning they had too few songs, they used to play a Diamanda Galas song from the “Litanies of Satan” release, and just stand there. “Put your head down and just play doom.” Lee gets a call on his cell phone, the window darkens from late afternoon to early evening. “The slowness was just vitally important to us – I don’t think we were looking to be unique, we just ended up – we obviously are unique, but we ended up that way because it was just important that we were slow.” Final words – “Doom will be doomed… don’t form a band!”

The DVD also includes the “Ebony Tears” video, which is full of regular video effects. Cool to watch a young Cathedral cavort around a forest and a graveyard with strange effects. One of the guitarists has a sticker on his guitar that says “Solitude.” Is that after the Black Sabbath song?

DVD reviews

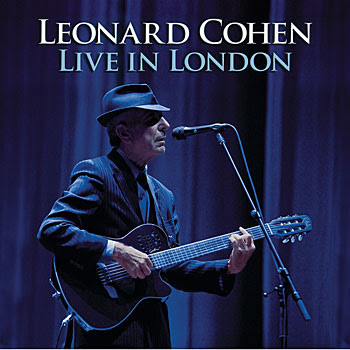

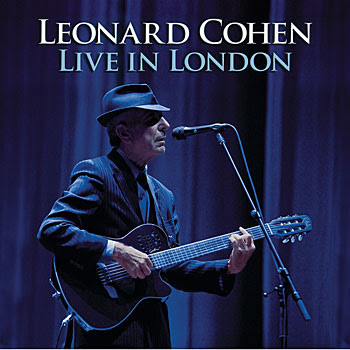

LC LIL

Leonard Cohen, Live in London – an amazing document, recorded mid-July, 2008 in London, when Leonard Cohen was doing a world tour. He was only 73 years old. And so, despite long years of semi-retirement, and many more spent on Mount Baldy becoming a Zen monk, he still came out and gave us his beautiful songs in that great virtuosic touring way where he was a ringmaster of an army of splendid musicians. We see this treatment from godfathers like David Gilmour and David Bowie, but Leonard Cohen has been doing it for many more years than those fellows and it’s incredible to behold. Cohen and his band play two sets – the first one is 57 minutes long, the second one is one hour, 40 minutes long (actually, the second set is one hour long, and the encores are another 40 minutes long). Cohen has so many amazing songs that the stream of major classics just goes on and on, until way, deep in the set when he plays “Take This Waltz,” which probably not one of his recognised classics. The production is rich and full, making it quite different from the “Field Commander Cohen: Tour Of 1979″ release, which is spare by comparison, focussing on acoustic guitar, duets with Jennifer Warnes, violin solos from Raffi Hakopian, and jazzy fretless bass.

His entire set Live in London is spotless, with the only real comparisons his amazing tours of the past. In this case, he starts his London set off with the words “Thank you so much, friends, so very kind of you to come to this…,” he’s drowned out in applause, and then the band kicks in to “Dance Me To The End Of Love”, with its electric clarinet, three backup singers, and the weird motions of 12-string guitarist Javier Mas (who also breaks out the banduria, laud, archilaud and is full of dramatic gestures). Curtains setting the mood onstage. Leonard Cohen sings, passionately gripping the microphone. “Thanks so much, friends. It’s wonderful to be gathered here just on the other side of intimacy. I’m so pleased that you’re here. I know some of you have undergone financial and geographical inconvenience. We’re honoured to play for you tonight.” Breaks into “The Future”, where he waters down the lyrics “Give me crack and anal sex” to “Give me crack and careless sex”. He has fun with the lyrics “white man dancing”, when he and the bass player do a little boogie, and when he alters a lyric “white women dancing”, the two white backup singers (Charley and Hattie Webb, the Webb Sisters) do a little jig. “It’s been a long time since I stood on a stage in London. It was about 14-15 years ago, I was 60 years old, just a kid with a crazy dream. Since then, I’ve taken a lot of Prozac, Paxol, Wellbuttrin, Exexor, Ritalin; I’ve also studied TV and the philosophies and the religions, and cheerfulness kept breaking through. But I want to tell you something that will not easily be contradicted – there ain’t no cure for love!” Breaks into a great sax intro for a stunning version of “Ain’t No Cure For Love,” followed by the best version of “Bird on a Wire” ever, toned down but with strong keyboards. This song, although it’s vastly famous, has never been a favourite of mine; nevertheless, it’s become gospel to the extent that I’ve met people who want these lyrics on their gravestones. Some drums and bass, swelling female backups, mandolin, great blues solo from Bob Metzger playing a semi-hollow body ‘72 Fender Telecaster Thinline. Sax solo.

The band plays “Everybody Knows”, after which Cohen announces “I wrote that song a long time ago with Sharon Robinson. More recently we wrote this one,” and they play “In My Secret Life”, a semi-duet between Cohen and Robinson, great blues guitars and organs, mild drums and bass; there’s a two-minute Spanish archilaud intro for “Who By Fire”, with its cool upright bass (great banging on the body for the outro bass roll), backup singer Hattie Webb on harp, Spanish solo on the larchilaud, a groovy organ solo, and Cohen plays the Godin classical guitar that is featured on the cover. Perfect – this has long been one of my favourite Cohen songs. He continues to play the Godin on “Hey, That’s No Way To Say Goodbye.” Great harmonica solo. Between-song banter is often a recitation of the vocals of the next song, and when he says “there is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in,” we know he’s going to sing “Anthem.” Great lyric – “While the killers in high places say their prayers out loud.” It’s the last song that they play before the intermission, although before they go offstage, Cohen introduces each of the members (he’d been doing it from time to time throughout the set as well).

After a break, they come out, and Cohen has a bit of an intro. “I was having a drink with my teacher, he’s 102 now. He was about 97 at the time. I poured him a drink, he clicked my glass and he said ‘excuse me for not dying.’ (laughter) I kind of feel the same way. I want to think you, not just for this evening but for the many years you’ve kept my songs alive.” Starts up a Technics keyboard, sings “Tower of Song”, with female backups. At his age, lyrics like “I ache in the places I used to play” probably have more meaning with each passing year. The song drones on at the end, with the backup singers going on and on with their “da doo dum dum dum, da doo dum dum.” Cohen launches into a long spiel: “Don’t stop, don’t leave me here alone, don’t ever stop. Sing me to bed and sing me through the morning, because I’m so grateful to you because tonight it’s become clear to me, tonight the great mysteries have unravelled and I’ve penetrated to the very core of things, and I have stumbled on the answer; and I’m not the sort of chap who would keep this to himself – do you want to hear the answer? Are you truly hungry for the answer? Then you’re just the people I want to tell it to. Because it’s a rare thing to come upon it, and I’ll let you in on it now. The answer to the mysteries…” and he makes a hand gesture towards the backup singers, “…is ‘da doo dum dum…”

Cohen does a short Spanish intro to “Suzanne” on the Godin and sings that marvelous song. There’s a great version of “The Gypsy Wife”, with a stunning mandolin freakout, Cohen playing the Godin throughout. Female vocals start, Cohen comes in after one line. There’s bass solo, but the camera has a lousy angle and we barely see it. Cohen and Robinson then launch in to “Boogie Street” (which, apparently, is named after a street in Singapore called Bugis Street -the local pronunciation of which sounds like “Boogie Stree”). Robinson takes over several verses, with Cohen doing backup. “Hallelujah” is splendid, with a groovy organ solo. “I’m Your Man” has a cool electric clarinet solo. He then continues with a spoken word segment that becomes a long recital, accompanied by light organ swells, of the lyrics of an alternate version of “A Thousand Kisses Deep” that is titled “Recitation W/N.L.”:

You came to me this morning and you handled me like meat

You’d have to be a man to know how good that feels, how sweet

My mirrored twin, my next of kin, I’d know you in my sleep

And who but you would take me in, a thousand kisses deep.

I loved you when you opened, like a lily to the heat

You see, I’m just another snowman standing in the rain and sleet

Who loved you with his frozen love, his second-hand physique

With all he is and all he was, a thousand kisses deep

I know you had to lie to me, I know you had to cheat

To pose all hot and high behind the veils of sheer deceit

Our perfect porn aristocrat, so elegant and cheap

I’m old, but I’m still into that, a thousand kisses deep

I’m good at love, I’m good at hate, it’s in between I freeze

I’ve been working out, but it’s too late, it’s been too late for years

But you look fine, you really do, they love you on the Street

If you were here I’d kneel for you, a thousand kisses deep

The autumn moved across your skin, got something in my eye

A light that doesn’t need to live and doesn’t need to die

A riddle in the book of love, obscure and obsolete

‘Till witnessed here in time and blood, a thousand kisses deep

And I’m still workin’ with the wine, still dancing cheek to cheek

The band is playing ‘Auld Lang Syne”, but the heart will not retreat

I ran with Diz, I sang with Ray, I never had their sweep

But once or twice they let me play, a thousand kisses deep

I loved you when you opened, like a lily to the heat

You see – I’m just another snowman standing in the rain and sleet

Who loved you with his frozen love, his second hand physique

With all he is and all he was, a thousand kisses deep

But you don’t need to hear me now, and every word I speak

It counts against me anyhow, a thousand kisses deep.

Incidentally, that is transcribed from the video itself; the lyrics that are provided by the DVD itself are different:

Recitation W/N.L.

You came to me this morning

And you handled me like meat

You’d have to be a man to know

HOw good that feels how sweet

My mirror twin my next of kin

I’d know you in my sleep

And who but you would take me in

A thousand kisses deep

I loved you when you opened

Like a lily to the heat

I’m just another snowman

Standing in the rain and sleet

Who loved you with his frozen love

His second-hand physique

With all he is and all he was

A thousand kisses deep

I know you had to lie to me

I know you had to cheat

To pose all hot and high behind

The veils of sheer deceit

Our perfect porn aristocrat

So elegant and cheap

I’m old but I’m still into that

A thousand kisses deep

And I’m still working with the wine

Still dancind cheek to cheek

The band is plainy Auld Lang Syne

The heart will not retreat

I ran with Diz and Dante

I never had their sweep

But once or twice they let me play

A thousand kisses deep

The autumn slipped across your skin

Got something in my eye

A light that doesn’t need to live

And doesn’t need to die

A riddle in the book of love

Obscure and obsolete

‘Till witnessed here in time and blood

A thousand kisses deep

I’m good at love I’m good at hate

It’s in between I freeze

Been working out but it’s too late

It’s been too late for years

But you look fine you really do

The pride of Boogie Street

Somebody must have died for you

A thousand kisses deep

I loved you when you opened

Like a lily to the heat

I’m just another snowman

Standing in the rain and sleet

But you don’t need to hear me now

And every wort I speak

It counts against me anyhow

A thousand kisses deep.

A few changes: other than the order of the sections, he mentions specifically Boogie Street (Singapore’s Bugis Street, which the song “Boogie Street” is supposedly named after, was in the past notorious for trans-sexual activity), and instead of “Diz” and “Ray”, he talks about Diz and “Dante.” Okay.

After that recitation, the most interesting original bit in the concert so far, the band breaks into “Take This Waltz,” a minor song from “Various Positions”, and not really one of my favourites. But here it sounds lovely, brought out by great accompaniment from Hattie Webb, whose gorgeous voice is heavenly.

Cohen tries to take leave of the stage, and even gets the band off, but is quickly back for an encore that is to last nearly as long as the second half of the concert (providing a full third act, it seems). The band breaks into a jaunty version of “So Long, Marianne”, then gets into a funky, waist-swinging “First We Take Manhattan”. Starts off with funky bass intro, then gets intense with lots of energy and dancing. The Web Sisters come through again as great, great backups. “Sisters of Mercy” is very good, with a nice opportunity for another archilaud solo (in nearly three hours of live music, you’re bound to get a few archilaud solos). To introduce “If It Be Your Will”, one of Cohen’s most beautiful songs, which he first sang with the sublime Jennifer Warnes, Cohen croaks out a verse or two before turning it over to the Webb Sisters, Charley working the mini-harp while Hattie takes the guitar (I think it’s a Gibson acoustic, not sure). The women re-define the concept of vocal harmonies, it’s stunning; and just to prove the point, when they finish their set, we get a shot of Cohen looking on, mesmerised. He snaps to it, and introduces “Closing Time”, probably the funniest song he’s ever written, and things get funky. He tries to make this his closing song (hint-hint), but all he does is run offstage and run back onstage again for a 10:30 version of “I Tried To Leave You” (hint-hint again), a gorgeous, undiscovered gem from “New Skin For The Old Ceremony”. This song is littered with solos – a guitar solo immediately followed by a sax solo, then an organ solo, then a Sharon Robertson vocal bit flowering up the first verse of the song. This is followed by more archilaud from Javier Mas, then “the sublime Webb Sisters” doing their mmm mmm mmm, ha ha ha…, gettin’ sexy ‘n’ hot ‘n’ heavy (most impressive), then a cool electric bass solo (first of the evening, remarkably), a light drum solo, then Cohen solos/improvs:

Goodnight my darlin’

I hope you’re satisfied

The bed is kind of narrow

But my arms are open wide

Yes and here’s a man, he’s still working for your smile

The song winds down after that… and the guys all ome out from behind the instruments to sing “Whither Thou Goest” as a vocal version – Robinson and Cohen’s voices come out clearest. The song lasts less than a minute, and the lyrics are:

Wherever thou lodgest, I will lodge

Thy people shall be my people

Whither thou goest, I will go

At the end of the film, we get a single credit:

“Sincerely, L. Cohen”.

Awesome.

Only complaint – Cohen introduces the band members too many times. He’s constantly adoring his band, his audience, and humbling himself; you’re also dying to hear him say, after he’s introduced the band, “… and my name is Leonard Cohen.” What applause that would get! Instead, we get “The sweet shepherd of stings, on the laud, Javier Mas; the master of breath on the instrument of wind, Dino Soldo; the signature of steady, on the pedal steel and the electric guitar, Bob Metzger; the prince of precision, our timekeeper – on the drums, Rafel Bernardo Gayol; on the Hammond B3 and the keyboards, the inpeccable Neil Larsen; my collaborator, the incomparable Sharon Robinson; Hattie and Charley Webb, the sublime Webb sisters; our guardian and sentry, the musical director on the upright and the electric bass, Roscoe Beck.” This is how he ends the concert (before the many encores), he did the same at the end of the first part.

Okay, maybe a few more complaints: the unnecessary mouth-harp solo in “So Long, Marianne”; the song has become weirdly cheerful, while it was always sort of wistful, this cheapens it a bit. I was also disappointed to not hear “The Story of Isaac” in this concert – was it too much of a downer? But it’s such a powerful song…

Book reviews

ND PM B

“Nick Drake, Pink Moon”, by Amanda Petrusich – Somebody had to do it – write a book about Nick Drake’s “Pink Moon.” Of course, with Drake dead for 35 years and nearly no information about him – no film footage of him exists, no live performance material, and barely any interviews – this is a hard book to write; never mind, though, this is a book from the 33 1/3 series of music geek pamphlets published by Continuum. This book is 118 sparse pages long, and divided into six chapters – named, of course, for the six first lines of the song’s lyrics – that are divided by one-page musings on Pink Moon by other musicians where they recount when they first heard Drake and what they thought about the music at the time, and how they’ve felt about it since. Seems that even famous musicians like Curt Kirkwood of the Meat Puppets first heard Drake after the VW ad that featured the title song (which, apparently, is called “Milky Way”).

The first chapter, “I saw it written” briefly recounts, over nine pages, the death of Nick Drake, before going into a bit about the recording, and then also into a bit about how author Pitchforkmedia.com Amanda Petrusich came to discover the music – and obsess over it, listening to it continuously on a Discman during her commute into New York City to attend classes at Columbia in 2001. “And I Saw It Say” is a short chapter of only four pages about Drake’s drug use (both recreational and prescribed), and his depression. “A Pink Moon Is On Its Way” is 14 pages about Drake’s childhood, tracing his birth in Rangoon to his countryside upbringing in Far Leys, and then his schooling, as he moved from being a lighthearted kid to a moody musician. There are descriptions of his recording of “Five Leaves Left” (which, apparently, comes from the message you’d see in a deck of rolling papers when only five pieces remain, which the author likens to the equivalent of calling your first album “tastes great, less filling” today), which included a bit of session work by Richard Thompson, and “Bryter Layer”, which called in the talents of John Cale, then working with Drake’s manager John Boyd on Nico’s “Desertshore” (I wonder how Drake and Nico would have gotten along – no evidence that they ever met, though). Cale, it seems, also introduced Drake to heroin. “None of You Stand So Tall” talks, over 24 pages of text, all about the “Pink Moon” sessions, and Drake’s low point in life when he wondered if anyone would ever listen to his songs; his management and his record company, at least, kept faith with him, and there was money to record this classic album (as well as four more songs after “Pink Moon” was done). Drake’s life, however, was deteriorating, and he was constantly stoned and barely coherent. Petrusich has this to say early in the chapter:

All over the song, Drake’s pronunciation is distorted and imprecise, and if he was having trouble speaking during the sessions it’s cringingly obvious here: Drake tries his best to choke out the record’s opening couplet (ostensibly, the lyric is “I saw it written / And I saw it say,” although it ends up sounding an awful lot like “Zoy written on a zoysay”), but he can’t seem to get his mouth to squeeze out the proper syllables in the proper order. The line is mumbled, incomplete, slurred.

I always thought that he was saying “Zoy written on a zoysay”.

Petrusich goes through the songs one by one, marveling at their spareness and the guitar virtuosity. Apparently, musicians all over the world attempt to re-engineer his tunings and fingerpickings and can’t quite do it. The songs are too hard to reconstruct. How this guy dreamed them out of the aether in the first place, while in the lowest of spirits and smoking crippling amounts of cannabis, is quite bewildering, if not miraculous. There’s a description of the photo shoot for the cover, which was never used – Drake, who is pictured on the cover of his first two albums, was practically comatose by that time, and didn’t really cooperate with the photographer – and the record company goes with the weird piece of art that is finally used. There is also the interesting bit of zeitgeist, talking about the political mood (Bloody Sunday), and the state of rock at the time (Led Zeppelin refused entry to Singapore to play a concert for looking too scruffy). It also obsesses with the re-issue and the rediscovery of Drake’s music a process that will not be complete until “Milky Way” comes out in November, 2000. ” “Pink Moon Gonna Get You All”, the longest chapter in the book at 35 pages, is devoted entirely to that commercial, its creation, moral issues around using a Nick Drake song to sell lifestyle, and its impact.

The “Milky Way” chapter is the best-researched of the chapters, and actually reads like it was written for another publication and popped in here for convenience, the other chapters written around this one as its core. It talks about the creative forces behind the VW ad, how Drake’s estate approved it, and the reaction of fans to the use of the song in a TV commercial; it also talks about the trend of using songs in commercials, starting with the arrogant mis-use of the Beatles’ “Revolution” in a Nike ad, to the new realities that many musicians now have their make-or-break based on a successful TV commercial. Weird. The conclusion of the chapter, or the way that it is written, is that Drake himself may have been happy with the ad, since it has finally given him what he was so achingly denied during his short recording career – popular recognition. The final chapter, “It’s a Pink, Pink, Pink, Pink, Pink Moon” is a three-page add-on that starts off ponderously quoting Sophocles, but doesn’t say anything at all.

But despite the success of the Nick Drake resurgence that came with the ad, it’s hardly deniable that no one will ever be able to say that they’ve discovered Nick Drake’s music entirely on their own – the way it used to be. Personally, I first heard about Drake from a fellow-guest at a wedding I went to in India in late 1999. She was not very musically knowledgeable, and when she mentioned Nick Drake I questioned whether she was talking about Nick Cave, ha ha; musically knowledgeable or not, she had one on me – I’d never heard of Nick Cave up to that point. Later in the new year, a package arrived with a tape of Nick Drake songs, and I’ve been hooked ever since. Every now and then I’ll turn a seemingly musically-knowledgeable person on to Nick Drake. Amazingly, and despite “Milky Way”, there are still people out there who have never listened to him.

Kirkwood’s brief piece on Nick Drake, by the way, is garbage. Why bother to include a piece of peripheral writing just because the author is a recognizable name?

BS MOR

“Black Sabbath, Master of Reality”, by John Darnielle – I read this wonderful, thin book in one day. It is not really about Black Sabbath’s third release “Master or Reality”, but about a fellow who spend two years in a mental hospital in his teens in the mid-80s, right when Black Sabbath was releasing “Born Again”, who relates that period of his life to the release. The book is good, ponderous, thinks about what Black Sabbath might mean to people, and explores the travails of the good messed-up teen. And this he is. The book mentions other Black Sabbath releases, and other bands that were near-contemporaries of Black Sabbath (Foghat, Rush, Mahogany Rush, etc), as well as some of the band’s heavy followers (Metallica, Slayer, Helix, etc), but nothing in the narrator’s world is more important than this band and this one release. Interestingly, the narrator gets some of his facts wrong – he doesn’t mention that guitarist Tony Iommi was in an industrial accident that severed the fingertips of his fretting hand, which is an important event in the band’s development, and he refers to Ozzy as the band’s lyricist, which I don’t think he was – but that’s probably part of having an unreliable narrator, not about the author not knowing these details. You’d have to assume that Darnielle, who is also a musician in his own right and fronts The Mountain Goats, would know all of this as real rock gospel.

Eric McCormack

“Inspecting the Vaults”, by Eric McCormack – Eric McCormack has been one of my favourite authors for a long time. Every summer when I go back to Japan I re-read his First Blast of the Trumpet Against The Monstrous Regiment of Women, which (for superstitious reasons) I won’t bring back to Singapore with me. I keep a copy of Inspecting The Vaults (which generously contains his first novel The Paradise Motel) with me here in Singapore and re-read it every so often. I still remember lying out on the field in front of the University of Waterloo Community Centre in 1989 as a university student reading the hardcover of The Paradise Motel (I’d splurged on it – I didn’t have much money in those days, of course, but as a new release the book was only available in hardcover) as I waited for my bus home for the weekend, and what a marvelous feeling it gave me.

Re-reading it now, I see that the stories aren’t as brilliant as I may have thought – they are extremely well written, and McCormack is an immaculate stylist, but there is a bit of thematic repetition, a morbid fascination with bitter ends, and superfluous robotic sexuality. I can see that McCormack is a consummate storyteller, just like so many of his characters, and he was born in Scotland but lives in Waterloo, like so many of his characters, and he (as an academic) likes to read, like so many of his characters. I think that this is a joke that Eric is playing on us, and it’s fantastic, even if it is repetitive.

As you read the stories, you can tell that he’s having a great time writing, pushing us one way and another with his stories, each of which he tries to make as different as can be (and yet never really succeeding – but don’t all great authors need to have a canon of like-themed books? McCormack is convinced, even if I am not).

The book that I have covers both Inspecting the Vaults and The Paradise Motel.

Inspecting the Vaults contains 21 stories and an exceedingly well-written introduction, where McCormack traces his life story, as he does with so many of his characters, from Scotland to Canada. The introduction is only three pages long, but it is better than nearly any of the fascinating stories in this collection. Starting off with a fantasy about a prisoner in a gulag, a voracious reader, who is kept in the dark for 23 hours and 59 minutes a day. For one minute, the guards turn on the lights – and he has an opportunity to read. The tale then goes into journeys, academia, and ideas. McCormack takes his existence for granted but wonders what book he’s reading. He then recounts an anecdote of reading as a youth (a letter arrived in the village, the first one ever, and was treated as an amazing object by all of the villagers) and then his arrival from dreary, slag-heap riddled mining villages Scotland to wide-open Canada (“one of the last of the good places”), and its many possibilities. These are the themes of his stories, and he mentions his love and interest in words and their power.

One of his passages about Canada is particularly enjoyable for anyone who’s ever been there or lived there, but is also telling about the way McCormack writes and thinks:

Eventually, in the Winnipeg winter of 1966, less pleasant realities struck. For the first time, my bare eyeballs felt the pain caused by freezing cold air. The hairs in my nose turned into wire. And that wineter, my bood Scottish overcoat, with its foam rubber lining, actually split in halves, right down the join at the back, when I took it off. It lay there ont he floor like the broken shell of a dead sea-creature. I think now I was shedding more than just a Scottish coat that day.

Inspecting the Vaults starts off with its title story, about the vault inspector in a remote area in some future (or past) dictatorship, where they lock up individuals for their strange and grotesque passions, not for any sort of real crime (although real criminals are also locked up there). In a simple fashion, the narrator inspector goes around all of the vaults, describes the vaultkeepers and the inmates, and recounts the strange, magical reasons that they are being interred. “The Fragment” is an academic mystery, where the narrator unearths the real meaning behind a fragment of a passage from Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, telling in the process the tale of freakish religious devotion (and its consequences) in a typically gory and violent manner.

“Sad Stories of Patagonia” is a 15-page tale that is probably the lynchpin of all of McCormack’s writing; it tells the tale of explorers in Patagonia on a futile quest for a living dinosaur, gathered at the end of the day around the campfire telling tales of tragedy. Two get their turn before Amos Mackenzie speaks up and tells of a tale of family horror from his hometown. The tale, and McCormack’s use of the tale to peel concepts of truth and reality, crops up again and again in his work. In fact, the search for information of the fate of Amos and his three siblings becomes the centre-point of The Paradise Motel, but the tale is also told in passing in all of his subsequent novels (when it crops up, as it always will, it begins to feel like family).

“Eckhardt at a Window” is a fascinating tale of a murder mystery – or was there really a murder? – and the undependability of information. “The One-Legged Men” is the very straight-forward tale tale of a mining disaster; the one-legged men are another recurring motif in McCormack’s writing, and they make their first appearance here. “Knox Abroad” is a piece of pseudo-history, recounting John Knox’s journeys, and the fantasy of how he would have behaved had he visited the New World. There is humour, violence, and all of the grotesque foibles of medieval life in an age of ignorance that arrogantly pretended knowledge. “Edward and Georgina” is about a brother and a sister that live together, told from the point of view of outside observers. What’s their story? Why has neither of them married? And why are they never seen together? “Captain Joe” is the metaphysical tale of a boy who went to sleep one day and woke up as a 60-year-old man.

“The Swath” is perhaps the best-written, amazing, and amusing tales in the collections. It reads more like straight reporting, but it tells a bizarre, magical tale, describing a gigantic trench 300 metres wide and 100 metres deep that suddenly appears in the earth; all that rock and dirt, and everything that is built on it, simply disappears. The swath moves around the earth, reconnecting to itself, and then it fills itself back in, all in the space of 24 hours. It’s an exciting tale, and McCormack recounts tales of the countries that it moves through, what happens to the oceans, and about the human reaction to it (unbelievable positive, actually). But no explanation is ever given; none is needed.

“Festival” is probably the story I like the least – I find its violence superfluous and unnecessary. “No Country For Old Men” (which, like the Cormac McCarthy book, comes from a line in the poem “Sailing To Byzantium” by William Butler Yeats), about World War I memories, is as short as it is hard to penetrate. “A Train of Gardens” comes in two parts, one as a bit of anthropology in the jungles of South America and other misadventures, while also setting up the seven-coach train of gardens. The second part of the story tells of the adventures inside the world of those garden train coaches. It is a cryptic and excitingly strange tale which, like all of McCormack’s tales, has no real resolution. “The Hobby” is a gorgeous, clever, short tale of a train hobbyist who rents a room in the basement of a family in rural Canada, and what he gets up to. The last line of the story is devastating. “One Picture of Trotsky” is just that, while “Lusawort’s Meditation” is the strange tale of a man who remembers the death of a friend, while “Anyhow in a Corner” is a peculiar interview with an author who is supported by a rich patron, and his musings on his condition and on the life of Sir Walter Scott. “A Long Day On The Town” is another tour-de-force tale, similar to the title tale, where the life stories of multiple individuals are tied together somehow, each of them fascinating. Check out the poet who became an anarchist who became a living bomb who became a stool pigeon who becomes a hobo. They, like the narrator, all end up in The Town. It makes me think of an HP Lovecraft story, such as “Shadows Over Inssmouth”, but much more to the point. “Twins” is the amazing tale of twins born in the same body, a concept covered by Stephen King in “The Dark Half”, but here it’s given the Eric McCormack treatment, which is just as dark, but of course it’s also very… different. “The Fugue” is an amazing tale of a crime told from three points of view – that of the unsuspecting victim, the killer, and the police detective rushing to prevent the crime. Brilliant.

The Paradise Motel is a novel of 205 pages. It starts off with a tale of narrator Ezra Stevenson, his parents, and the return of his long-lost grandfather. Where did he go? Why did he abandon his family? And why did he only come back to die? The drama is incredible in this little short story within a novel (the novel contains at least a dozen tales that could stand on their own). Stevenson travels the world researching the fates of Esther, Zachary, Rachel and Amos McKenzie, their first initials making up his own first name, Ezra. He comes close to tracking all of them down, but something is wrong. By the end, there is no resolution, but it’s all still a great story.

The Lightning Thief

“The Lightning Thief’, by Rick Riordan – My friend Margaret gave this book to Zen because I told her he likes Beast Quest books. Zen and I read this together because although it was a bit too difficult for Zen to read on his own, he was very excited about reading the story. As I read it, we came upon more and more Greek gods, so now Zen knows a little bit about those great tales. We talk about it a lot now and have a lot of fun.

The book is very clearly modeled on Harry Potter, and has a lot of similarities – a guy who didn’t know his father (Harry didn’t know either of his parents), he discovers he has special abilities and a birthright, he goes to a hidden school for people like him, he makes powerful friends (mentors and protectors and sage teachers) and powerful enemies, he surprises himself by defeating people seemingly more skilled than him, he picks up a goofy male sidekick and a bratty/brainy female sidekick.

But the story is fun, and it is also conscious to be not too similar to Harry Potter. For example, they don’t go to a school for magical people but a summer camp for magical people. The difference is, however, that the concept of leveraging the tales of the Greek gods gives the feel of reviving a long-neglected legacy, or picking up a good story where it left off. It’s been done before, of course, but this still feels pretty natural.

The story itself is not bad, and Percy travels to Hades and back with his new friends, but one thing is a bit irritating – the villain and his intentions was broadcast so widely that it was really shocking when Percy was surprised by the villain’s revelations at the end. No matter, however, I’m looking forward to seeing the movie now, and to reading the second book.

BNIACBH

“Big Nate – In a Class by Himself”, by Lincoln Peirce – This book models itself clearly on the Diary of a Wimpy Kid books, but is not nearly as funny. Big Nate is a bit of a wimp, and a day in the life of Big Nate is not all that interesting for me, but Zen did enjoy reading it.

MB

“Motherless Brooklyn”, by Jonathan Lethem – My friend Matt gave me this book this summer, and after I read it I realised that this was the second book I’ve read by Jonathan Lethem, who also wrote the incredibly strange This Shape We’re In. This story is about a young man, part of a team of four “detectives”, all orphans, who do work for the Brooklyn hustler who took them out of the orphanage. The narrator, Lionel Essrog, also suffers from Tourette’s Syndrome, the condition of tics and verbal outbursts, which people in his vicinity either understand or don’t. When his boss is murdered, he goes on the case to try to find the murderer; the murderer is obvious, so the story is more about finding out why he was murdered. But even more, the story is about Lionel, and understanding how he lives, how he controls his tics, and what kind of a future he has waiting for him. Orphans with Tourettes probably have a hard lot in life, and since Lionel is probably also the world’s worst detective he doesn’t have much going for him there either. He doesn’t really do anything, he stumbles onto the story somewhat haphazardly, and hardly gets any information out of anybody.

The book wasn’t supremely satisfying, but nonetheless well-written. And although the story is a bit of a non-story, the way it is told and the way the story unfolds is good writing. It’s certainly more straight forward than This Shape We’re In.