Persepolis is the wonderful comic book by Marjane Satrapi, an Iranian artist now living in Paris who was about 10 years old when when the Islamic revolution swept over her country, deposing the tyrant king and bringing with it its own set of problems – the imposition of religious laws and law enforcement, a war with Iraq, and an “inner war” against the people of Iran by the people of Iran. The art is brilliant, with simple line drawings done in inky black and white as to imitate inkblock style that is highly expressive and emotional. There are two English-language books of Persepolis, eaqch of which contains themed episodes of 7-9 pages, and I have read the first one. The movie combines both into one narrative.

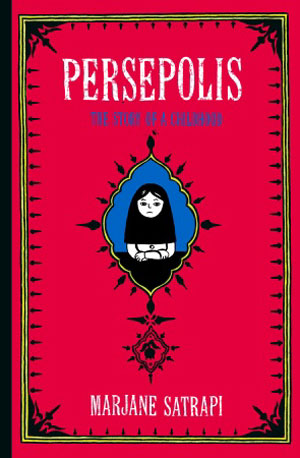

Pbook

Persepolis (book) – The key phrase of the book, repeated more than once, is “One can forgive, but one should never forget.” The book depicts Marjane’s childhood in a privileged family, and goes all the way up to her flight to Vienna to live with an uncle. Attending classes in a French school, the first pages depict the stress of being streamed into same-sex schools and forced to wear a veil, and what this meant for society. Some protest against the veil, some protest for the veil. Society becomes morbid, with children saying things like “execution in the name of freedom” in their games. Mom’s pic was taken and published in magazines. The book is full of wonderful doodles on various pages, like one showing the contrast between an Islamic life of tradition and a modern life of education and enablement, another one of her grandfather as an idealised prince with a sword-wielding lion, family faces coming to a sleeping dreamer, kids walking down a forest lane, the family on a flying carpet going off to spain with a dancing women hidden among the squiggles, a rush of cars among a fire, an army of self-flagellating schoolgirls (?!?!), explosions destroying an army of martyr children with gold-painted plastic “keys to heaven” (“they told the boys that if they went to war and were lucky enough to die, this key would get them into heaven”), depictions of the rush down stairs during an air raid alert (bodies rushing down multiple staircases) and the aftermath of phone calls of friends and relatives checking up on each other.

Satrapi tends to intersect the horror of the outside world with the horror in the family world, but sometimes she also balances the horror of modern Iranian history with banalities or superficialities (like a punk party, or shopping for jeans). There’s the horror of the Rex, when imperial soldiers locked film-goers into a cinema and set it on fire. At age six, Marjane wanted to be a prophet, and talked to God. Her family had a maid, a Cadillac, she wanted to be a Marxist and share this with everyone. “The Bicycle” is history and politics, Arabic invasions and all the rest of it. Descartes/Marx/apple sequence is hilarious. A history of demonstrations, and stories of her grandfather – the intellectual son of an emperor who became a prime minister under the Shah, but as a Marxist was imprisoned in a flooded cell, suffering his whole life. “That’s really the probe of our country: only a prince can allow himself to have a conscience.” There’s the surreal episode of the mob celebrating the martyrdom of a young man killed by government forces, sweeping up an old man also who’d died of cancer, also a “martyr.” The parents laugh, young Marjane is confused that death can be funny. A tale for the ages, there’s the maid who falls in love with the neighbour’s boy, but they can never be together as she’s a peasant. “We were not in the same social class, but at least we were in the same bed.” The war with Iran started, but “in fact it was really our own who had attacked us.” Black Friday killings, and the release of two political prisoners who are friends of the family, Siamak and Mohsen. Uncle Anoosh is a hero, he tried to establish the independence of Iranian Azerbaijan. What he suffered under a Russian wife was worse than prison. Former revolutionaries became the sworn enemies of the republic (?!?!?). There was no life waiting for them after being released from the Shah’s prisons, as the zealot rulers dispatched fundamentalist assassins to rub them out (things never change). The crimes continue as they shut down the universities, “better to have no students than to educate future imperialists.” There’s the surrealism of the Islamic argument that womens’ hair emanates rays that excite men. One page shows the “uniforms” of 1980s Iranian men and women, be the fundamentalists or modern. “Islam is more or less against shaving.” No short sleeves (hair) or neckties (imperialist) for men. Ulp!!

There are whole sections chronicling violence against women, including the practice of not executing a condemned woman with her virginity intact, the brutal language of zealots towards women they deemed not suitably modest, and the chiding of women from the south as “sluts”. Ridiculous. “Guns may shoot and knives may carve, but we won’t wear your silly carves” protest chant is met with bullies shouting “The scarf or a beating.” How can you fight stupidity? But sometimes there is humour in the situation, like one started by Marjane, and her father’s response:

The iraquis have always been our enemies. They want to invade us.

And worse – they drive like maniacs.

There’s the sad story of the girl whose father, a pilot, was locked up for being part of a coup d’etat. He’s freed so that he can fly bombing runs against Iraq. He doesn’t come back. Marjane commends her for her hero father, she says “I wish he were alive and in jail rather than dead and a hero.” The country suffers oil shortages and a refugee influx when the refinery city is bombed, impacting family life on all levels. Then there’s the martyr and the war dead, and Marjane’s rebellion against her female principal, to whom father says “if hair is as stimulating as you say, then you need to shave your beard.” Social dynamics change as neighbour spies against neighbor, and the Satrapis tape up their windows to protect from prying eyes… and enjoy chess, card games, drinking, music and dancing during their parties (and to protect from shards of glass when they are shattered by missile blasts. One time, when the sirens wailed, a mother of a newborn thrusts her baby into Marjanie’s arms as she runs for the shelter. “Since that day I’ve had doubts about the so-caleld maternal instinct.” Argues with mom after cutting class. “My mother used the same tactic as the torturers.” This leads to her first cigarette and the end of her childhood at age 14. The insanity of the times is tremendous: “We refuse this imposed peace!” “To die a martyr is to inject blood into the veins of society.” Yuck! The regime’s survival depended on the war, it later admitted, despite a million dead. The horror, the horror…

Uncle Taher sickens and dies from the internal war and the teenagers executed in the streets for their rebellion, they visit the hospital and see the victims of chemical attacks (made by the Germans, the victims are sent to Germany for treatment – and study – as veritable guinea pigs… the horror, the horror). The tale of the trip to Turkey to get Kim Wilde and Iron Maiden posters. At the black market for music, the guys are selling tapes by Estevie Vonder, Jikael Mackson, and others. Marjanie is stopped by a coterie of harridans chastising her “punk rock” Nike sneakers, and her Michael Jackson pin (which she claims is Malcolm X, the leader of the Black Muslims, because “back then, Michael Jackson was still black”). Awesome.

Harridan – Why are you wearing these “punk” shoes?

Marjanie – What punk shoes? These are sneakers!

Harridan – Shut up! They’re punk.

Marjanie – (In comment: It was obvious that she had no idea what punk was.)

SCUD missiles and the end of the Baba-Levy family, Jews whose lineage had survived in Iran for 3,000 years. As Marjanie goes off to Paris, there are highly emotional farewells, including one with her wonderful grandmother, who keeps her breasts so firm and round by soaking them in ice water for ten minutes every morning and every evening (!!!) and smelling nice by lining her bra with jasmine flowers (!!!). She gives Marjanie a great speech:

In life you’ll meet a lot of jerks. If they hurt you, tell yourself that it’s because they’re stupid. That will help keep you from reacting to their cruelty. Because there is nothing worse than bitterness and vengeance… Always keep your dignity and e true to yourself.

Just that quote is worth the price of admission, as is Majanie’s response: “I smelled my Grandma’s bosom. It smelled good. I’ll never forget that smell.” The final page is the sad, heartbreaking farewell at the airport and a mother’s collapse. I simply must read Persepolis 2!

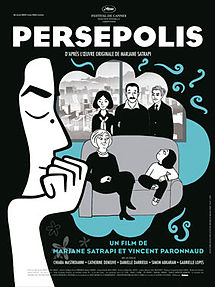

Pmovie

Persepolis (film) – The film combines the stories of the books of Persepolis 1 and Persepolis 2 English-language books. It’s a nice enough film, of course, since it tells Satrapi’s magical story, including all of her whimsy and the violence and terror and uncertainty of the era. Someone took the decision to jazz up the story, and even change scenes such as when Marjane’s father tells the story of the Shah’s father becoming the emperor under a British-supported coup-support-for-oil deal, injecting old Persian imagery. There are funky effects, editing, and the judicious use of colour. Certain details have been left out, such as the bombing of the Baba-Levy’s house, or that unforgettable scene in the airport when Marjane looks back to see that her mother has collapsed and her father is carrying her (shiver!!!!). Details about Taher’s Russian wife have been omitted too, which is probably a good thing – his comment was very cruel. Ultimately, the feeling is that visual texture has been added at the expense of narrative texture, and somehow this style also removes the stark beauty of the original comic which was one of its key strengths, making the film ultimately unsatisfying in my view; despite this, however, it is true that Satrapi herself was one of the directors of the film, so you can hardly complain that the book’s been unjustly messed around with.

The voice actors in the film are notable, with Gena Rowlands playing Marjane’s mother in the English version, Sean Penn the father, Iggy Pop as Uncle Anouche, and the wonderfully-named Amethyste Frezignac as the young Marjane (the French version includes luminaries like Catherine Deneuve as Marjane’s mother.

There are a few things that I didn’t see in the book, as treats from Marjane, such as the comments on Japanese in one scene where a Godzilla movie appears on Iranian television, “all the Japanese seem to do is hack each other up with samurai swords or run away from gruesome monsters.” Weird TV drama lines, “you cursed hairdresser, you are not worthy of my son!” There’s the surreal scene of the art class with students drawing veiled models. Grandma’s pipe is surreal and boss, and her schooling is so dramatic and poetic, like the flowers she puts in her bra so that she smells nice. “You’re crying because you made a mistake. It’s always hard to admit it when you’ve grown up.” Marjane’s parents, so central to the first half of the film, become secondary characters, although they still have great lines, like “Iran is not for you, I forbid you to return.” And so it begins.