KC

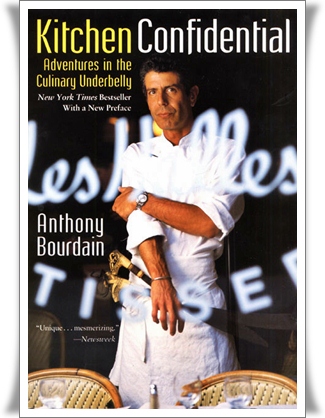

Kitchen Confidential, by Anthony Bourdain – I love this book. Bourdain can really write! He’s not just a kitchen personality, or a TV personality, he’s a literary personality!!

A friend of mine passed me his book, and I quickly got lost in those strange tales of a punk rock chef allying himself with the short order swashbucklers who inhabit the realm and keep it going, who keep it crazy – who keep it real. From his savagely bourgeois upbringing, to the wild days of his apprenticeship, to his lessons in finding his path (I don’t know if I could ever do the same, to tell you the truth), I just enjoyed the journey and how he described it.

For all of his swagger, Bourdain can be remarkably humble when talking about the really great chefs, managers, mentors and influencers that he admires (there are quite a few, although not as many as he really knocks down to their knees). Then there’s the wild rides of the kitchen hands:

It was Friday, an hour before service, when I was introduced to Tyrone the broiler man, whom I’d be trailing. Looking back, I can’t remember Tyrone as being anything less than eight feet four, four hundred pounds of carved obsidian, with a shaved head, a prominent silver-capped front tooth and the ubiquitous fist-sized gold hoop earring. While his true dimensions were probably considerably more modest, you get the picture: he was big, black, hugely-muscled, his size 56 chef’s coat stretched across his back like a drumhead. He was a gargantua, a black Viking, Conan the Barbarian, John Wayne and the Golem all rolled into one.

Sounds like a pretty vivacious kitchen ride. Amazing. But it gets very real when Bourdain burns himself and asks for burn cream and a bandage.

Tyrone turned slowly to me, looked down through bloodshot eyes, the sweat dripping offf his nose, and said, “Whachoo want, white boy? Burn cream? A Band-aid?”

Then he raised his own enormous palms to me, brought them put real close so I could see them properly: the hideous constellation of water-filled blisters, angry red welts from grill marks, the old scars, the raw flesh where steam or hot fat had made the skin simply roll off. They looked like the claws of some monstrous science-fiction crustacean, knobby and calloused under wounds old and new. I watched, transfixed, as Tyrone – his eyes never leaving mine – reached slowly under the broiler and, with one naked hand, picked up a glowing-hot sizzle-platter, moved it over to the cutting board and set it down in front of me.

He never flinched.

Wow.

With all of his ego and scorn, Bourdain does give credit where credit is due, and one of my favorite passages in the book is when he’s talking about Bigfoot, the employer who pulled him out of the gutter and gave him a chance when he was going through a very bad drug phase.

In Bigfootland you showed up for work fifteen minutes before your shift. Period. Two minutes late? You lose the shift and are sent home. If you’re on the train and it looks like it’s running late? You get off the train at the next stop, inform Bigfoot of your pending lateness, and then get back on the next train. It’s okay to call Bigfoot and say, “Bigfoot, I was up all night smoking crack, sticking up liquor stores, drinking blood and worshipping Satan… I’m going to be a little late.” That’s acceptable – once in a very great while. But after showing up late, try saying (even if true), “Uh… Bigfoot, I was on the way to work and the president’s limo crashed right next to me… and I had to pull him out of the car, give him mouth-t-mouth… and like I saved the leader of the free world, man!” You, my friend, are fired.

And while he can be prone to doing that lame “as I mentioned earlier” thing nobody should ever do, especially not in print (we’ve been reading, we know you wrote it earlier), his descriptive passages are awful and marvelous:

It was, as I’ve said, hot. Ten minutes into the shift, the cheap polyester whites we all wore would be soaked through with sweat, clinging to chest and back. All the cooks’ necks and wrists were pink and inflamed with awful heat rashes; the end-of-shift clothing change in the Room’s fetid, septic locker rooms was a gruesome panorama of dermatological curiosities. One saw boils, pimples, ingrown hair, rashes, buboes, lesions and skin rot of a severity and variety you’d expect to see in some jungle backwater. And the smell of thirty not-very-fastidious cooks – their sodden work boots and sneakers, armpits, cologne, fungal feet, rotten breath – and the ambient odor of moldering three-day-old uniforms, long-forgotten pilfered food stashed hidden in lockers to which the combination was unknown, all combined to form a noxious, penetrating cloud that followed you home and made you smell as if you’d been rolling around in sheep guts.

Disgusting tales of kitchen hijinks are amazing, and some cool practical jokes, like forming realistic-looking amputated body parts out of sweet dough.

A waiter would open a reach-in in the morning to find a leaking, torn fingertip, Band-Aid still attached, pinioned to a slice of Wonder Bread with a frilled toothpick. A floor manager would be called down to the kitchen in the middle of a dinner shift to find one of us standing by a bloody cutting board, red-smeared side towel wrapped around a hand, and as they approached, one of the grisly fingers would drop onto his foot. We experimented constantly, finding to our delight that not only did the sweet dough look like flesh when shaped and colored correctly, but it drew flies like the real thing! Left overnight at room temperature, these fake digits could develop into a truly horrifying spectacle.

Each chapter is somewhat self-contained and is a journey through Bourdain’s childhood education of food, his college years, his first jobs in a kitchen, and includes wild ruminations on cooking school, the development of professional kitchen culture in the US, his various New York City jobs, and his late-night misadventures. He also has great instructive passages about planning his menus, buying the right kitchen equipment, managing a kitchen, dealing with owners, praising the work of his pirate crewe of Hispanic kitchen staff, controlling theft and other criminal activity among his staff, and some interesting words on the operations of rival chefs. He includes a fair bit on how-not-to-run-a-restaurant.

There’s also some cool history-of-New-York stuff in his book that you must marvel at:

The most truly amazing feature of my temporary kingdom was to be found deep in the bowels of the Paramount Hotel, through twisting catacomb-like service passageways adjoining our downstairs prep kitchen. If one squeezed past the linen carts and discarded mattresses and bus trays from the hotel and followed the waft of cold, dank air to its source, one came upon a truly awe-inspiring sight: the long-forgotten Diamond Horseshoe, Billy Rose’s legendary New York nightclub, closed for generations. The space was gigantic, an underground Temple of Luxor, one huge uninterrupted space. The vaulted ceiling was still decorated with Renaissance-style chandeliers and elaborate plasterwork. The original rhinestone-aproned stage, where Billy Rose’s famously zaftig chorus line once kicked, was still there, but the giant space where the horseshoe-shaped bar once stood was empty, the floorboards torn up. Around the edge of the cavernous chamber were the remnants of private booths and banquettes where Legs Diamond and Damon Runyon and Arnold Rothstein and gangsters, showgirls, floozies and celebrities – the whole Old Broadway demimonde of the Winchell era – used to meet and greet and make deals, place bets, listen to the great singers of the time and get up to all sorts of glamorous debauchery. The sheer size, and the fact that you had to slip through a roughly smashed-in wall to enter the chamber, made the visitor feel he was gazing upon ancient Troy for the first time.

It’s great that he has such cool taste in music – working in his kitchen must be a blast:

I’ve assembled a pretty good collection of mid-seventies New York punk classics on tape: Dead Boys, Richard Hell and the Voidoids, Heartbreakers, Ramones, Television and so on, which my Mexican grill man enjoys as well (he’s a young head banger fond of Rob Zombie, Marilyn Manson, Rage Against the Machine, so my musical selections don’t offend him).

He also explains the rude language of the kitchen:

The rules can be confusing. Cabron, for instance, which translates roughly to “your wife/girlfriend is getting fucked by another guy right now – and you’re too much of a pussy to do anything about it” can also mean “my brother,” depending on the inflection and tone. The word “fuck” is used primarily as a comma. “Suck my dick means “Hang on a second” or “Could you please wait a moment?” And “Get your shit together with your fucking meez, or I come back there and fuck you in the chulo” means “Pardon me, comrade, but I am concerned with the state of readiness for the coming rush. Is your mise-en-place properly restocked, my brother?”

Pinche wey means “Fucking guy”, but can also mean “you adorable scamp” or “pal.” But if you use the word pal – or worse, the phrase my friend – in my kitchen, it’ll make people paranoid. My friend famously means “asshole” in the worst and most sincere sense of that word. And start being too nice to a cook on the line and he might think he’s getting canned tomorrow. My vato locos are, like most line cooks, practitioners of that centuries-old oral tradition in which we – all of us – try to find new and amusing ways to talk about dick.

He’s great at describing his comrades in ways that seem unbelievable (but which may actually true), and none more so than Adam Real-Last-Name-Unknown:

I may have wanted Adam dead a thousand times over. I may have imagined, even planned his demise – torn apart by rabid dogs, his entrails snapped at by ravenous dachshunds, chained to a pillory post and flogged with chains and barbed wire before being drawn and quartered with chains and barbed wire – but his bread and his pizza crust are simply divine. To see his bread coming out of the ovens, to smell it – that’s deeply satisfying, spiritually comforting waft of yeasty goodness; to tear into it, breaking apart that floury, dusty crust and into the ethereally textured interior… to taste it is to experience real genius. His peasant-style boules are the perfect objects, an arrangement of atoms unimproveable by God or man, pleasing to all the senses at once. Cezanne would have wanted to paint them – but might not have considered himself up tot he job.

Towards the end of the book he has great chapters talking about his time in Tokyo, learning a bit about the country and seeing how people there cook, as well as searching the country for great food, is very interesting to me, since I’ve lived in Japan; to his credit, he doesn’t try to peer into the the mind of the Japanese or to make any pronouncements on the nation’s character, and therefore doesn’t embarrass himself with the type of flaky wrong-minded stuff you’d find in a book by Pico Iyer or Paul Theroux or dozens of other bozos. No, he’s only there to write about the food, and the journey reaches its climax at the fish market.

Tsukiji, Tokyo’s central fish market, puts New York’s Fulton Street to shame. It’s bigger, better and – unlike its counterpart in Manhattan – a destination worthy visiting if only to gape.

I arrived by taxi at four-thirty in the morning. The colors of the market alone seemed to burn my retinas. The variety, the strangeness, the sheer volume of seafood available at Tsukiji amounted to the colossal Terrordome of mind-boggiling dimensions. The simple awareness that the seafood-crazy Japanese were raking, dredging, netting and hooking that much stuff out of the sea each day gave me pause.

A Himalayan-sized mountain of discarded styrofoam fish boxes greeted my arrival, as well as a surrounding rabbit warren of shops, breakfast joints and merchants servicing the market. The market itself was enclosed, stretching seemingly into infinity under a hangar-type roof, and I will tell you that my life as a chef will never be the same again after spending the morning – and subsequent mornings – there. Scallops in snowshoe-sized black shells lay atop crushed ice; fish, still flopping, twitching and struggling in pans of water, spat at me as I walked down the first of many narrow corridors between the vendors’ stands. Things were different here in that the Japanese market workers had no compunction about looking you in the eye, even nudging you out of the way. They were busy, space was limited, and moving product around, in between sellers, buyers, dangerously careening forklifts, gawking tourists and about a million tons of seafood, was tough. The scene was riotous: eels, pinned to boards by a spike through the head, were filleted alive; workers cut loins of tuna off the bone in two-man teams, lopping off perfect hunks with truly terrifying-looking swords and saws that, mishandled, could easily have halved their partners. Periwinkles, cockles, encyclopedic selections of roes – salted, pickled, cured and fresh – were everywhere, as was fish still bent from rigor mortis: porgy, sardines, swordfish, abalone, spiny lobsters, giant lobsters, blowfish, bonito, bluefin, yellowfin. Tuna was sold like gems – displayed in light boxes and illuminated from below, little labels indicating grade and price. Tuna was king. There was fresh, dried, cut, number one, number two, vendors who specialised in the less lovely bits. There were hundreds, maybe thousands of gigantic bluefin and bonito, blast-frozen on faraway factory ships. Frost-covered two hundred- to three hundred-pounders were stacked everywhere, like stone figures on Easter Island, a single slice taken from near the tail so that quality could be examined. They were laid out in rows, built up into heaps, sawed into redwood-like sections, still frozen, hauled about on forklifts. There were sea urchins, egg sacs, fish from all over the world. Giant squid as long as an arm and baby squid the size of a thumbnail shared space with whitebait, smelts, what looked like worms, slugs, snails, crabs, mussels, strip and everything else that grew, swam, skittered, crawled, snaked or clung near the ocean floor.

Finally, he offers a list of advice to someone who, despite all warnings, still wants to work in the restaurant industry. Most of them are common-sensical, but a few are funny:

2. Learn Spanish!

11. Avoid restaurants where the owner’s name is over the door. Avoid restaurants that smell bad. Avoid restaurants with names that will look funny or pathetic on your resume.

14. Have a sense of humour about all things. You’ll need it.

Great book. Read it!