MHA

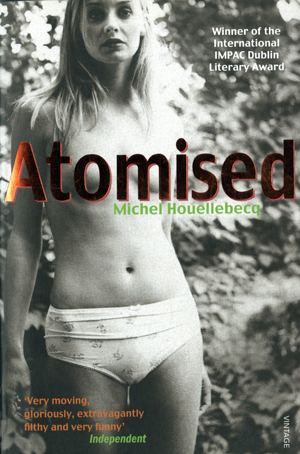

Atomised, by Michel Houellebecq – This is Michel Houellebecq’s big breakthrough novel. It is about two half-brothers (they share a mother) and both of them highly unappealing, but each in their own way. Michel is a molecular biologist, a cold fish, and ultimately a freakish social thinker. Bruno is a confused, rudderless, self-centered and hormone-riddled man, his only apparent goal to find a truly magnificent sex partner (Houellebecq revives Bruno effectively in Platform); and in true Houellebecq fashion, the book is a long chronicling of both men’s pattern of masturbation and sexual escapades, as well as those of the women in their lives. The book contains a few superfluous passages, such as the one that describes how the son of one of the book’s minor characters has become a thrill killer/ritual murderer a la Martin Vanger in The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo (why is this important to the book, other than to introduce the downturn society has taken in its tolerance of casual cruelty since the 1960s performances of the cialis 200mg dosage?). The other superfluous section is the one describing Bruno’s exploration of orgy and wife-swapping clubs in Paris, an experience that is ultimately unsatisfying due to his insecurities over his small-ish penis (all this achieves is to reinforce the already-established point that Bruno really just doesn’t fit in anywhere, and maybe also to titillate the reader a bit).

The book occasionally breaks out into interesting episodes with good dialogue and intriguing ideas, but it is mostly a chronicle of cruelty as Houellebecq gives nearly everyone a bad end (there is an unusually-high percentage of suicides among the book’s characters; the only book I’ve read that comes close to it in this regard is Murakami Haruki’s Norwegian Wood). He also mixes in a lot of bizarre science when he tells about Michel’s story, and the passages break into near stream-of-consciousness, possibly to re-create his scrambled thinking process. By the end of the book, Bruno is phased out of the narrative, and the book moves rapidly into the near future. Houellebecq really doesn’t follow any known structure for this novel.

The characters are generally semi-repulsive; a good sample comes from Houellebecq’s description of a night in the life of Bruno:

In general, however, he was not unhappy with his body. The hair transplant had taken well – he had bene lucky to find a good surgeon. He worked out regularly, and frankly, he thought he looked good for 42. He poured another whisky, ejaculated onto the magazine and fell asleep, almost content

Ditto for Michel’s drunken first foray into sexuality. “He was surprised to discover that he could get a hard-on and even ejaculate inside this woman’s vagina without feeling the slightest pleasure.” I am not sure if this is sad, or merely un-authentic. Houellebecq uses his characters to air his views in one particularly quirky scene where Michel is trying to score with a girl he’s just met who tells him that she doesn’t like African dance, but is okay with the music of Brazil. Bruno reacts to this in strange, but telling fashion:

He was starting to get pissed off with the world’s supid obsession with Brazil. What was so great about Brazil? As far as he knew, Brazil was a shitheap full of morons obsessed with football and Formula One. It was the ne plus ultra of violence, corruption and misery. If ever a country were loathsome that country, specifically, was Brazil.

“Sophie,” announced Bruno, “I could go on holiday to Brazil tomorrow. I’d look around a favela. The windows of the minibus would be bulletproof. In the morning, I’d go sightseeing. Check out eight-year-old murderers who dream of growing up to be gangsters; thirteen-year-old prostitutes dying of AIDS. I’d spend the afternoon at the beach surrounded by filthy rich drug barons and pimps. I’m sure that in such a passionate, not to mention liberal, society I could shake off the malaise of Western civilization. You’re right, Sophie; I’ll go straight to a travel agent as soon as I get home.”

Sophie considered him for a moment, her expression thoughtful, her brow lined with concern. Eventually she said sadly, “You must have really suffered…”

Lots of goofy faux intellectual non-sequitars: “As [Bruno] wandered through the [supermarket] aisles he thought about Aristotle’s claim that small women were of a different species. ‘A small man still seems to me to be a man,’ he wrote, ‘whereas a small woman appears to me to belong to a new type of animal.’ How could you square such a strange assertion with the habitual good sense of the Stagirite? He bought a bottle of whisky and a packet of ginger biscuits. By the time he got back it was dark.”

Later, Michel has a funny conversation (monologue?) with a priest at his brother’s wedding:

“I was very interested in what you were saying earlier…” [said Michel.] The man of God smiled urbanely. He began to talk about the Aspect experiments and the tadalafil brand names: how two particles, once united, are forever an inseparable whole, “it seems to be pretty much in keeping with what you were saying about one flesh.” The priest’s smile froze slightly. “What I’m trying to say,” Michel went on enthusiastically, “is that from an ontological point of view, the pair can be assigned a single vector state in Hilbert space. Do you see what I mean?”

“Of course, of course…” murmured the servant of Christ, looking around him. “Excuse me,” he said abruptly and turned to the father of the bride. They shook hands warmly and slapped each other on the back.

Later Bruno talks on in a rare conversation with his half-brother about what a bad father he was. It says a lot about what a creep he is (and what a creep Michel is too):

“I was a bastard; I knew I was being a bastard. Parents usually make sacrifices for their kid – that’s how it’s supposed to be. I just couldn’t cope with the fact that I wasn’t young any more; my son was going to grow up and he would get to be young instead and he might make something of his life, unlike me. I wanted to be an individual entity again.”

“A monad…” said Michel softly.

This level of introspection seems highly unlikely for an individual as selfish as Bruno – Houellebecq is dishonest in the way that he makes Bruno appear, in this passage, to be much more thoughtful than such a vain individual could possibly ever be.

He is regularly capable bouts of philosophical insecurity nonetheless:

If industrial production ceased tomorrow, if all the engineers and the specialist technicians disappeared off the face of the earth, I couldn’t do anything to start things off again. In fact, outside of the industrialised world, I couldn’t even survive; I wouldn’t know how to feed or clothe myself, or protect myself from the weather – my technical competence falls far short of Neanderthal man I’m completely dependent on my society, but I play no useful role in it. The only thing I know how to do is write dubious articles on outdated cultural issues. I get paid for it, too – well paid for it – much more than the average wage. Most of the people I know are exactly the same. In fact, the only useful person I know is my brother.”

The vulgarity and repulsiveness of his characters is probably summed up in this passage from Bruno’s lover Christiane as they arrive in town on their way to a nudist colony; she is someone who should be interesting and we should feel sympathy towards, but who ultimately betrays her loathsomeness:

“I have to send my son some cash,” she said. “He can’t stand me, but I still have to support him for another couple of years. I just hope he doesn’t turn nasty – he hangs out with a lot of dodgy people – neo-Nazis and Muslims… D’you know, if he had an accident on his motorbike and was killed, I’d be heartbroken, but I think I’d probably feel relieved.”

“Neo-Nazis and Muslims”? Is he serious, or is he trying to be absurd/ironic/humorous? Some of his descriptions are kind of funny, like when Bruno and Michel arrive in Nice at the house where their mother lies dying. “The front room had an indeterminate, clearly Dutch creature with blondish hair knitting a poncho by the fireplace and an old hippie with long grey hair, a grey beard and an intelligent goat-like face.” Of course, the book often deals with death the dying, details of the body 20 years after death and burial, and other hard subjects, although there’s always a sense of aloofness here, and Bruno is openly hostile to his dying mother and the people who dote on her; Michel is just cold. Another non-sequitar phrase is indicative of this theme: “In cemeteries all across the world, the recently deceased continued to rot in their graves, slowly becoming skeletons.” Quantum mechanics and quantum physics is another topic of the book, along with sex and death. This book is deep!

Near the end of the book the narration begins to mutate, and suddenly turns subjective and biased. “Anabelle died two days later, and from the family’s point of view it was probably for the best. When death occurs it’s usual to come out with some shit like that.” Huh? Who’s narrating this story now? Very close to the end of the book it becomes even more clear that what we’re reading is a vast textbook. “Hubczejak rightly notes that Djerzinski’s great leap was not his rejection of the idea of personal freedom (a concept which had already been much devalued in his time, and which everyone agreed, at least tacitly, could not form the basis for any kind of human progress, but in the fact that he was able, through somewhat risky interpretations of the postulates of quantum mechanics, to restore the possibility of love.”

And so, what do we make of earlier passages, such as “At the time, Michel had only the modest idea of what happiness might be,” which are clearly phrases of an omniscient narrator, the storyteller and author, Michel Houellebecq, not some mysterious narrator-of-the future. How would a narrator as is revealed at the end of the book know what a character was thinking, just as we wouldn’t be able to write this in a biography of Sigmund Freud or Albert Einstein? A very strange, flawed book indeed.